The economic impacts of COVID-19 relief programs directly intersect with tax law. As the system becomes more stressed for tax revenue, discussions about seemingly immutable topics are bound to return. What was once forsaken is up for discussion. The passive investment income of private corporations is one such topic. I discuss this below.

The July 2017 Consultation Paper

In July 2017 the Department of Finance (“Finance”) released a Consultation Paper (“Paper”) titled Tax Planning Using Private Corporations.[1] Therein, Finance detailed three concerns about how individuals, in their capacity as “owner-managers” of private corporations, were using their corporations to avoid tax. Their concerns were:

- Income Sprinkling,

- Holding Passive Investments in a Private Corporation,

- Converting Income into Capital Gains.

This post focuses on the second point regarding passive investments.

The Taxation of Passive Investment Income

There are two types of private corporations: private corporations and a narrower subset known as Canadian-controlled private corporations (“CCPC”). There are also two corporate tax rates applicable to “business income” loosely defined: the general 26.5% rate, and the lower rate of 12.2% (in Ontario). The relevant corporate tax rate depends on the type of private corporation and the type of income earned. For example, while it is common to say CCPCs are taxed at 12.2%, this only holds true for the “active business income” of a CCPC, and even then only up to the business limit of $500,000. Other business income, of a CCPC and non-CCPC, is subject to the general rate of 26.5%.

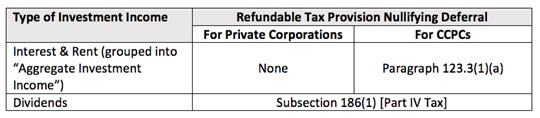

The important point about corporate rates – 26.5% or 12.2% – is that they are lower than the top marginal rate applicable to personal income of 53.53%. This rate gap creates the opportunity for tax deferral and therefore incentivizes holding passive investments in a corporation. However, the benefits of deferral are largely nullified by refundable taxes on the income from those investments. See the chart below.

The Problems Noted by Finance

In spite of the above, in its reporting on passive investments, Finance outlined two limitations thought to be subverting the purpose of lower corporate rates. I describe them as:

- Source of Capital for Passive Investment (was characterized as a major problem)

- Source-Independent Refundability of 123.3 tax (was characterized as a minor problem)

Ultimately, following critical commentary and widespread public debate, Federal Budge 2018 fell flat on the major problem, resolving only the minor problem. The minor problem was addressed by way of new provisions which streamed the RDTOH accounts into the new ERDTOH and NRDTOH accounts.[2]

Source of Capital for Passive Investment

While the major problem can be articulated in writing, for the layman and fellow tax-newbie, I diagram it below:

The flowchart above traces a CCPC’s income. A CCPC has several pools of after-tax income which contribute to its retained earnings, and thus its internal financing potential. Finance argued that the red coloured path above provides an improper advantage and is a misuse of after-tax business income. That path is:

- The CCPC earns business income which is taxed at corporate rates,

- A greater initial investment portfolio is made available to the owner-manager because he incurs corporate rates, not the top-marginal personal rate,

- That investment portfolio earns aggregate investment income taxed at 50.17%,

- Notwithstanding the 50.17% rate shown above, the result is a greater after-tax amount of aggregate investment income (relative to an individual investing directly),

- There is a compounding effect when the loop repeats on re-investment.

It is important to recognize that it is the source of investment capital (i.e. after-tax business income) that results in the targeted mischief, not the earning of investment income. The investment income is adequately dealt with by the refundable tax at s 123.3, which approximates the top personal marginal rate.

Was Finance’s Concern Legitimate?

The Joint Committee of the Canadian Bar Association and Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (“Joint Committee”) responded to the Consultation Paper.[3] They provided evidence which countered the examples provided by Finance.

One of Finances examples considered the passive investment of $100,000 at 3% for 10 years, comparing the after-tax value of the investment if it was made by an individual directly (from his employment income; 53.3% tax rate) versus a CCPC (from its active business income; 12.2% tax rate). By retaining investment yield in the corporation for 10 years, thereby deferring personal tax, corporate net worth exceed personal net worth by $4,885. However, the Joint Committee showed that under-integration actually made the corporation worse-off for the first 6 years of the 10 year period.

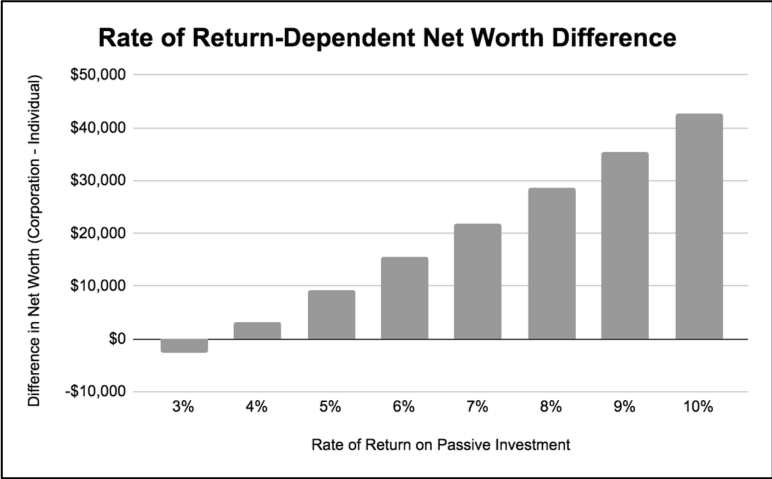

The Joint Committee also provided its own comparative example wherein $100,000 of active business income is invested at 3% for 10 years, but with an annual addition to the investment pool of $100,000. The tax rate used was 26.5%. Under this example, under-integration was once again proffered as the culprit for the corporation being worse-off – the owner-manager collects $500,827 and the individual $501,864. However, as I have graphed below, the difference in net worth over a 10-year period is highly sensitive to the assumed rate of return.

Professional Corporations as the True Target of Finances Concern

The Joint Committee’s use of a 26.5% corporate rate was premised on the knowledge that the corporate advantage is more pronounced when a 12.2% rate is used. They also noted that:

“aspiring entrepreneurs can be expected to take into account all features of the Canadian tax system that might apply if their venture proves successful. Furthermore, the separate analysis of the general [26.5%] and small business rates [12.2%] helps illustrate the extent to which the source of the “problem” perceived by the Government may in fact be the SBD [12.2%] itself, rather than a more systemic problem.”

By showcasing a benign 26.5% example and disregarding examples with different rates of investment return (i.e. rates higher than 3%), the Joint Committee advocated to relegate the problem to the small business deduction (i.e. one that only applies to the 12.2% rate). This led to the enactment of paragraph 125(5.1)(b) which claws back a CCPCs business limit in proportion to aggregate investment income exceeding $50,000.

The Joint Committee left to the last section of their comments any discussion about professional corporations. Professional Corporations (“PC”) are CCPCs. However, because many PCs participate in large partnerships, their access to the 12.2% rate is already limited by the specified corporate partnership rules which force a sharing of the business limit. Hence the 26.5% rate is more relevant to those PCs and 125(5.1)(b) does not affect them as seriously as would Finance’s other proposals. If one accepts that there is still an advantage at the 26.5% rate, then the proliferation of PC’s operating in large partnerships is still in need of resolution.

On the flip side, it is important to remember that size matters. Solo-practices of one PC and small partnerships of PCs do still make use of the 12.2% rate. However, before one pounces on their tax deferral, consider where such practices exist. These smaller and less affluent practices exist in rural and small communities. Are they truly deserving of penalty? Or should tax deferral be viewed as a quid pro quo for their provision of services in remote areas? Has 125(5.1)(b) already done the job of penalizing them?[4]

Further still, could it be argued that tax deferral is the only true benefit of incorporation for professionals. While incorporation typically provides shareholders the benefit of limited liability, such insulation is not absolute for the PC shareholder-service provider. The professional can still be personally liable where that liability arises out of the core business (i.e. professional negligence). Where such a fundamental benefit of incorporation is fettered as such, surely the relative significance of a tax benefit is enlarged. What do you think?

Non-CCPC Private Corporations Not Subject to s 123.3 Tax

If CCPCs are advantaged relative to an individual, then an even greater advantage exists for the owner-managers of non-CCPC private corporations. This is because non-CCPC private corporations are not covered by s 123.3. This means their aggregate investment income is taxed at 39.5%, not 50.17%. If a non-CCPC invests $100,000 taxed at 26.5% for 10 years at a 3% rate of return, their portfolio would be $99,018 after integration. An individual’s portfolio would only be $87,984. The difference of $11,034 is 2.26x greater than if a CCPC was used.

Business Income vs. Employment Income

Finance’s concerns were all premised on an equality between employment income and business income. Is it true that employment income should be treated the same as business income in respect of the decision to invest? Here, the Joint Committee made strong logical arguments about why business income is different from employment income. After all, employment income is only earned out of business income. See the Joint Committee’s report for great commentary on this point.

It seems to me that Finance’s call for equal treatment of business and employment income was at least partly informed by the goal of dividend integration. The equation “Corporate Taxes on Income + Personal Taxes on Dividends = Personal Taxes if Income Earned Directly” starts off this section of the Consultation Paper. What is the best way of explaining that dividend integration targets a different concern? What are dividends, legally and conceptually?

- Mohammad Ahmad (JD Candidate, OHLS Class of '21)

[1] https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/fin/migration/activty/consult/tppc-pfsp-eng.pdf

[2] https://www.budget.gc.ca/2018/docs/tm-mf/tax-measures-mesures-fiscales-2018-en.pdf at 20.

[3] https://www.cba.org/CMSPages/GetFile.aspx?guid=355b8a11-7399-4f30-9ec5-bf0c9ab8dee9

[4] This point brought to my attention in an email from Professor Scott Wilkie.