How does the Income Tax Act know if a corporation has the capacity to pay an eligible dividend? If an eligible dividend is good for the taxpayer because it means less personal tax payable, surely the Act must police this area of the law. Below, I detail the policing regime and the purposes motivating associated penalty taxes.

Eligible Dividend Designations

A corporation can designate all or a portion of a dividend to be an eligible dividend by way of a written notification to receiving shareholders [s 89(14)]. Public corporations satisfy this requirement by making a one-time blanket designation that all of their dividends are eligible. Individual shareholders like receiving eligible dividends because it means less tax payable. However, if the amount of a designation results in an “excessive eligible dividend designation” [“EEDD”; s 89(1)], the paying corporation incurs Part III.1 tax. This tax is equal to 20% of the excessive amount.

When does a dividend designation become excessive? What it is the mischief which deems it worthy of penalty? The answers to these questions depend on (a) an understanding of dividend income integration, and (b) the type of after-tax income from which the dividend is sourced.

(a) Integration Generally

A policy choice of our tax system is that, in some respects, the amount of tax paid on income should be similar irrespective of the form through which it is earned (i.e. by a corporation or by an individual directly). This is why dividends paid to individuals, sourced from after-tax corporate income, should not be taxed at the full top-marginal rate of 53.53% (in Ontario). This “integration” between the personal and corporate tax system is achieved by a gross-up and credit mechanism which I explored in a previous blog post.

(b) GRIP and LRIP – The After-Tax Income Pools

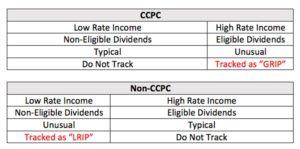

There are two types of dividends: eligible and non-eligible. Whether a dividend is eligible or non-eligible (and hence the extent of personal level gross-up/credit) depends on how the after-tax income funding its distribution was taxed. Is the after-tax corporate income the product of heavy or light taxation? If heavy, when that income is dividended out, the recipient should get a greater gross-up/credit so that less personal tax is paid (relative to a dividend from lightly taxed corporate income). As one can imagine, there must be some sort of track-and-match system in the Income Tax Act. The Act accomplishes this through the GRIP and LRIP tax attributes. As depicted in the tables below, tracking just two accounts across various corporations is a clever way to keep track of high vs. low rate after-tax income. For CCPCs “unusual” income is that income which was taxed at the general rate, relative to active business income taxed at a low rate. The after-tax amount of this income is tracked in the “general rate income pool” or GRIP. For non-CCPC’s (ex. private corporations, public corporations, non-public non-private corporations), unusual income is low rate income. The after-tax amount of this income is tracked in the “low-rate income pool” or LRIP. A typical example of LRIP is an intercorporate dividend received by the corporation on shares of a CCPC which was not designated as eligible.

Mischief 1 - GRIP based EEDDs of CCPCs

A CCPC can only declare eligible dividends to the extent that it has GRIP. If a CCPC does not have GRIP, the only after-tax income it has accumulated was subjected to a low corporate rate. If a dividend from this income was permitted an enhanced gross-up/credit by being designated eligible, there would also be low personal tax. Low corporate tax plus low personal tax is a misalignment that must be corrected to preserve the integrity of integration. Hence, the formula for the EEDD of a CCPC is the amount by which any eligible dividends exceed GRIP at years-end. The mischief targeted by an EEDD here is payor generated over-integration and lost tax revenue. I would not describe this as a deferral because deferral benefits presuppose that the correct rate of tax will eventually be collected at some future date. Here, absent corrective measures, an incorrect rate would be applied and not recovered.

Mischief 2 – LRIP based EEDDs of Non-CCPCs

For a non-CCPC, eligible dividends are the typical type of dividend. How then can there be an excessive eligible dividend designation? The formula for LRIP based EEDDs makes it so that a non-CCPC must deplete its LRIP before any eligible dividends can continue to be paid free of Part III.1 tax. It is an ordering rule. The mischief here is not that there is no “heavily” taxed after-tax income to match with the eligible dividend. Indeed, high-taxed income is the default for non-CCPC’s (see charts above). The mischief is the possibility of indefinitely deferring personal level tax on lightly taxed corporate income.

The Rate of Part III.1 Tax

Regardless of which type of corporation (or account – GRIP or LRIP) generates an EEDD, the penalty is 20%. Are both mischiefs noted above equally offensive? Do they both deserve a 20% tax?

Negative GRIP

The formula for GRIP of a CCPC is A – B. GRIP may be negative.

(a) The A in A – B

The A term represents after-tax income taxed at a high corporate rate.

One might think GRIP can be negative where the A term is negative, by virtue of one of A’s components being negative in an amount that overwhelms other positive components. Specifically, this might happen when the CCPC’s “adjusted taxable income” is negative. However, such a result is precluded by s 257.

(b) The B in A – B

The B term is meant to reduce present-year GRIP as a consequence of loss carry-backs effected in the tax year. This makes conceptual sense. If a loss carry-back reduces previous year incomes, then the GRIP of those previous years is retroactively lower than calculated in those tax years. Why? Mechanically, loss carry-backs reduce previous year “full rate taxable incomes” which serves as a proxy for a reduced A term in the previous year(s). We might say the B term performs a three-year retroactive sweep to capture the effects of loss carry-backs.

GRIP can be negative where loss carry-backs are significant (i.e. B is high) and the CCPC did not earn current year income taxed at a high corporate rate (i.e. A is low).

(c) No Immediate Consequence of Negative GRIP

The formula for an EEDD of a CCPC is the amount by which an eligible dividend designation exceeds GRIP (i.e. Dividend – GRIP). If an eligible dividend is paid against a GRIP of zero, then the entire dividend is excessive. If GRIP is negative, then by way of a double-negative, the excessive amount is actually greater than the dividend itself [i.e. (Dividend) – (– GRIP)]. However, the actual formula for EEDD prevents this outcome by using “greater than” language to disallow a negative GRIP from entering the formula in the first place.

Therefore, a corporation does not incur Part III.1 tax on the absolute value of negative GRIP. Stated otherwise, while a corporation is fully punished for exceeding its capacity, it is not further punished for its negative capacity. Instead, the only “penalty” of negative GRIP is that the corporation will need to rebuild its GRIP back to zero. In the interim, is it appropriate to disregard the negative portion? Is the Act tolerating a loss in tax revenue from over-integration (see “Mischief 1” above). Is the result of there being no immediate consequence of a negative GRIP consistent with the ordering rule which forces a non-CCPC to immediately payout a non-eligible dividend when it has LRIP? Perhaps there other consequences associated with loss carry-backs which operate to trade-off this inconsistency, if it is one. Maybe the time-value of money is not significant enough a benefit for this to be an issue. Or is there a liquidity concern, that a negative GRIP having taxpayer will not have funds to pay tax on the negative portion.